Yanigata are interesting items associated with kodogu. At first glance they might appear to be molds for casting fittings, but they are made in positive relief. Another thought might be that they are forms for raising a thin sheet of metal, but they have much more detail than that would require and are much too fragile to survive it.

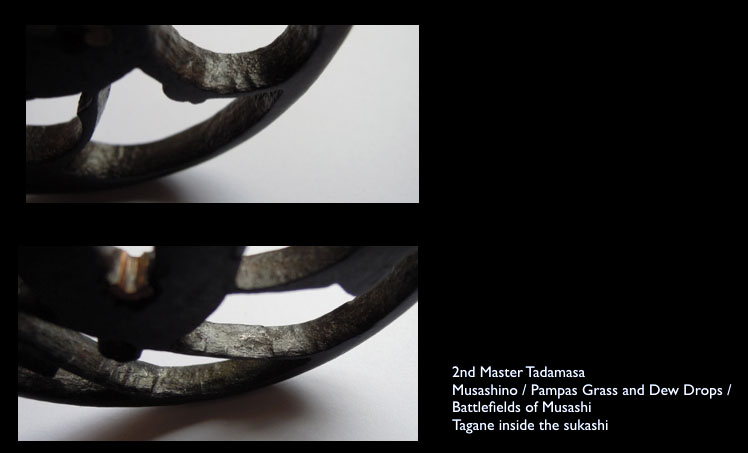

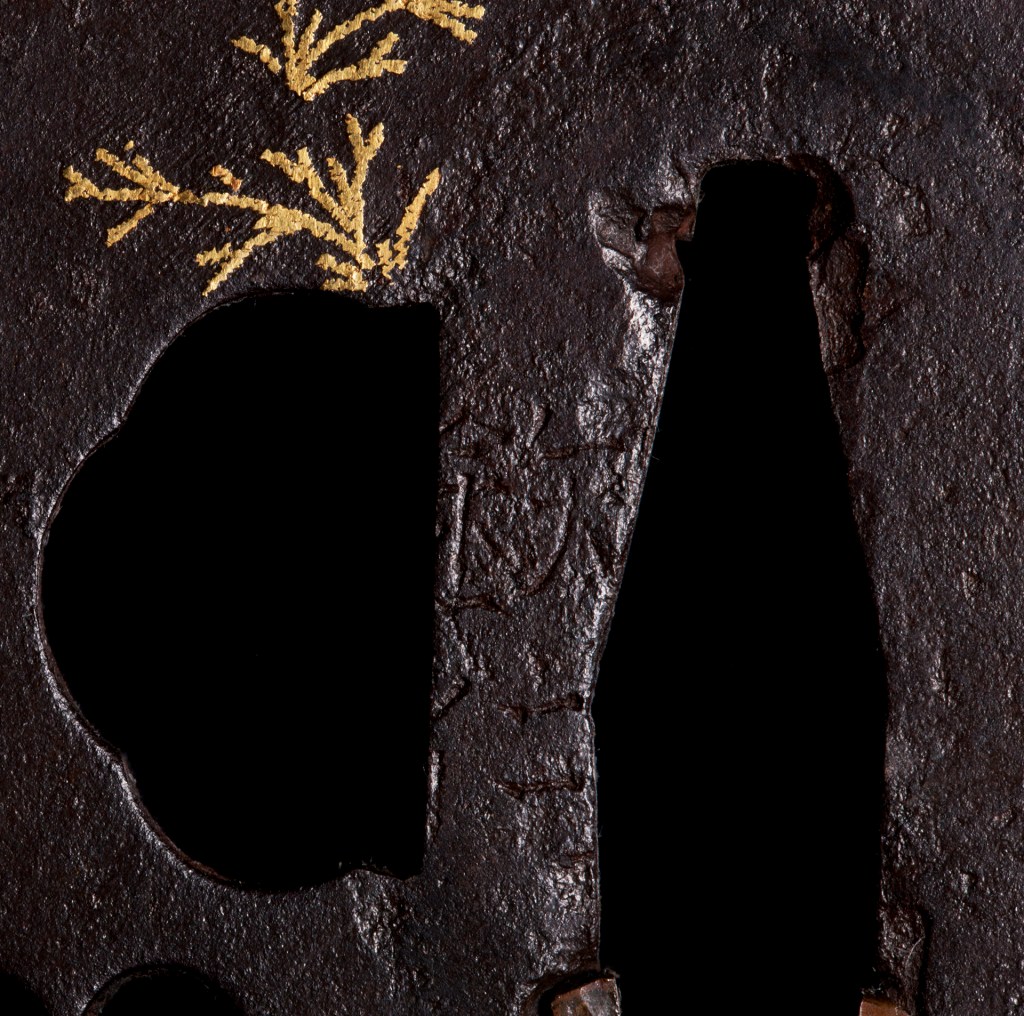

This example is from a kozuka with the dragon and ken motif frequently found in Goto work. As can be seen here, larger yanigata sometimes have distorted lines that would not make them useful for creating copies.

There is a lot of detail to be found in the nanako, dragon scales, etc., but some of the low points are a bit indistinct and this is a clue as to how these were made. As far as we know, yanigata are replicas of finished kodogu that were retained by their makers for reference, perhaps for study by contemporary and later generation students.

A completed fitting would be pressed into a pliable clay mixture called nengata to form a negative impression. When dried the resulting mesugata would be used as a mold to cast the yanigata from pine resin, possibly mixed with a solvent or other materials. A release agent of some sort was likely required for one or both steps to get things to come apart cleanly. I would guess that the bent lines and cracks in the above example formed during the cooling of the resin, but I have not tried this process at home. Does anyone know more about the materials and methods?

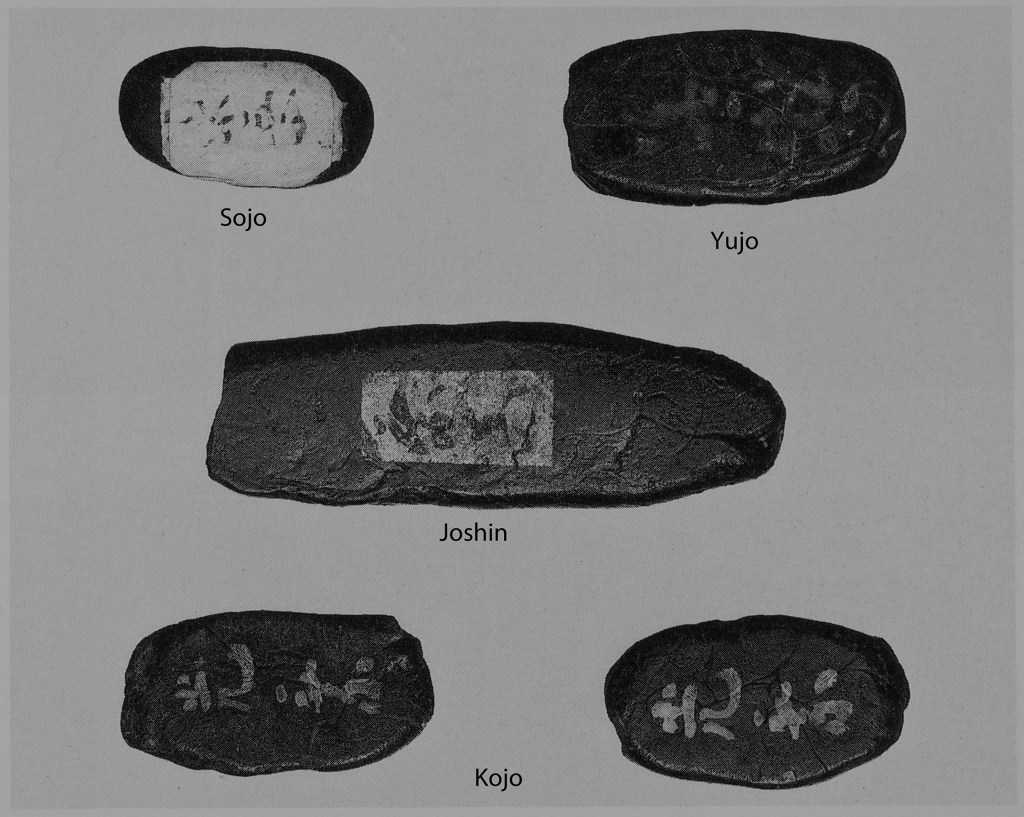

The back sides show evidence of kneading, sometimes retaining fingerprints. A friend mentioned imagining that holding the tsuka of an old koshirae is like shaking hands with the original owner. These fingerprints come another step closer.

The backside of the yanigata isn’t formed from contact with the original clay mold though, so it would presumably come from working with the resin while still in a plastic state to get it into a practical shape. The finished item is fairly light weight and tapping a yanigata makes a sound and feel similar to a low fired clay piece.

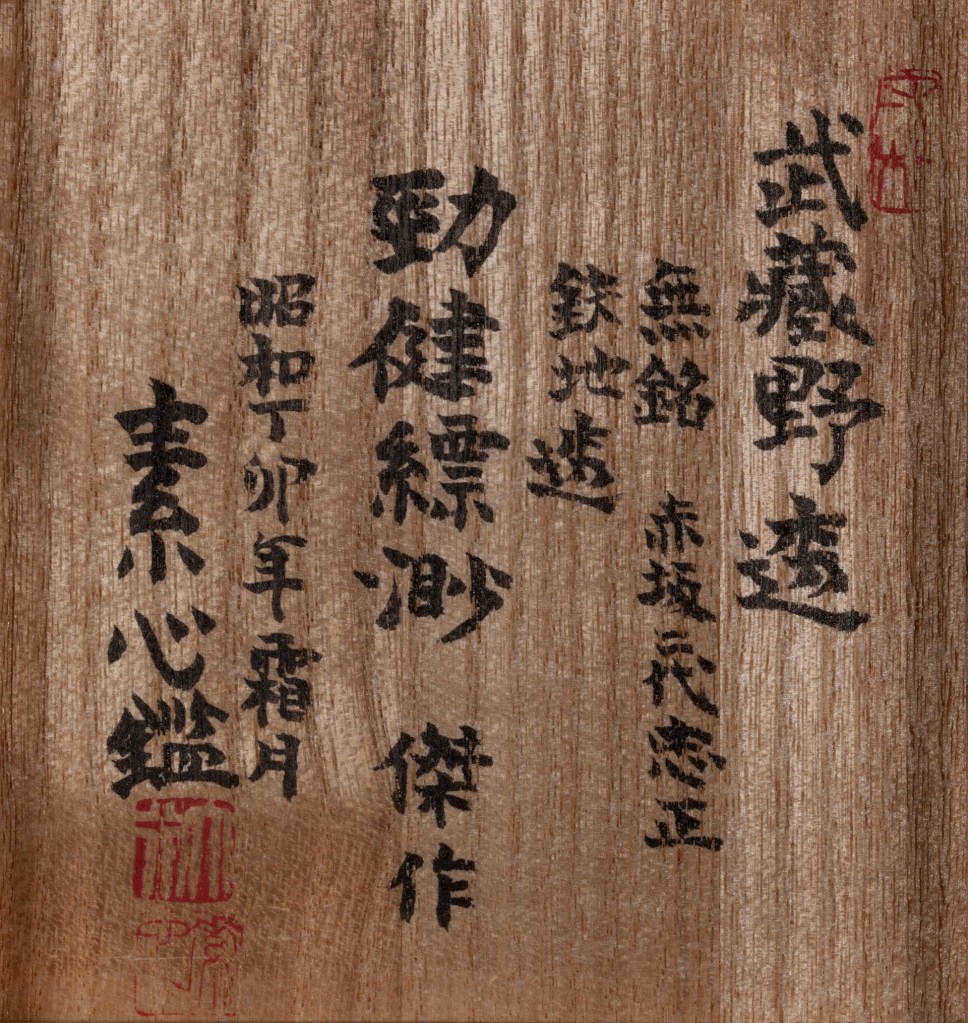

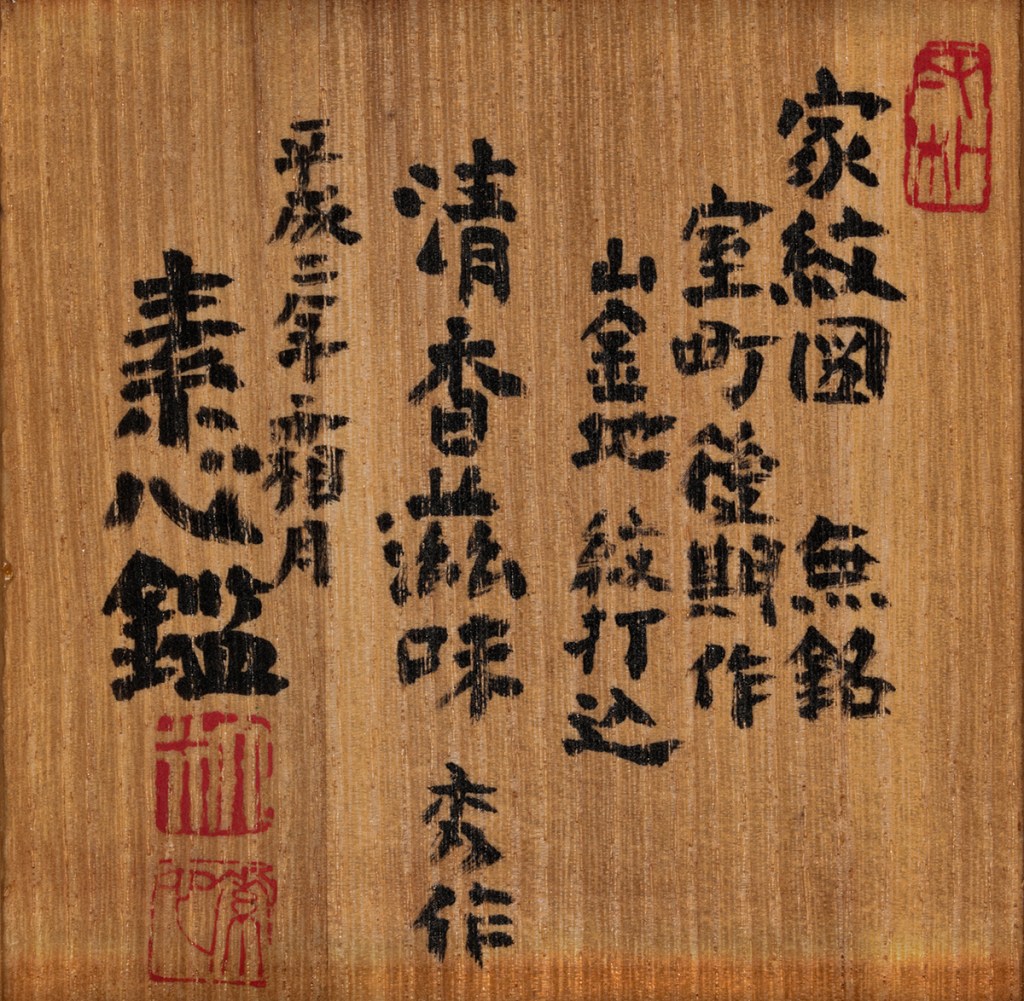

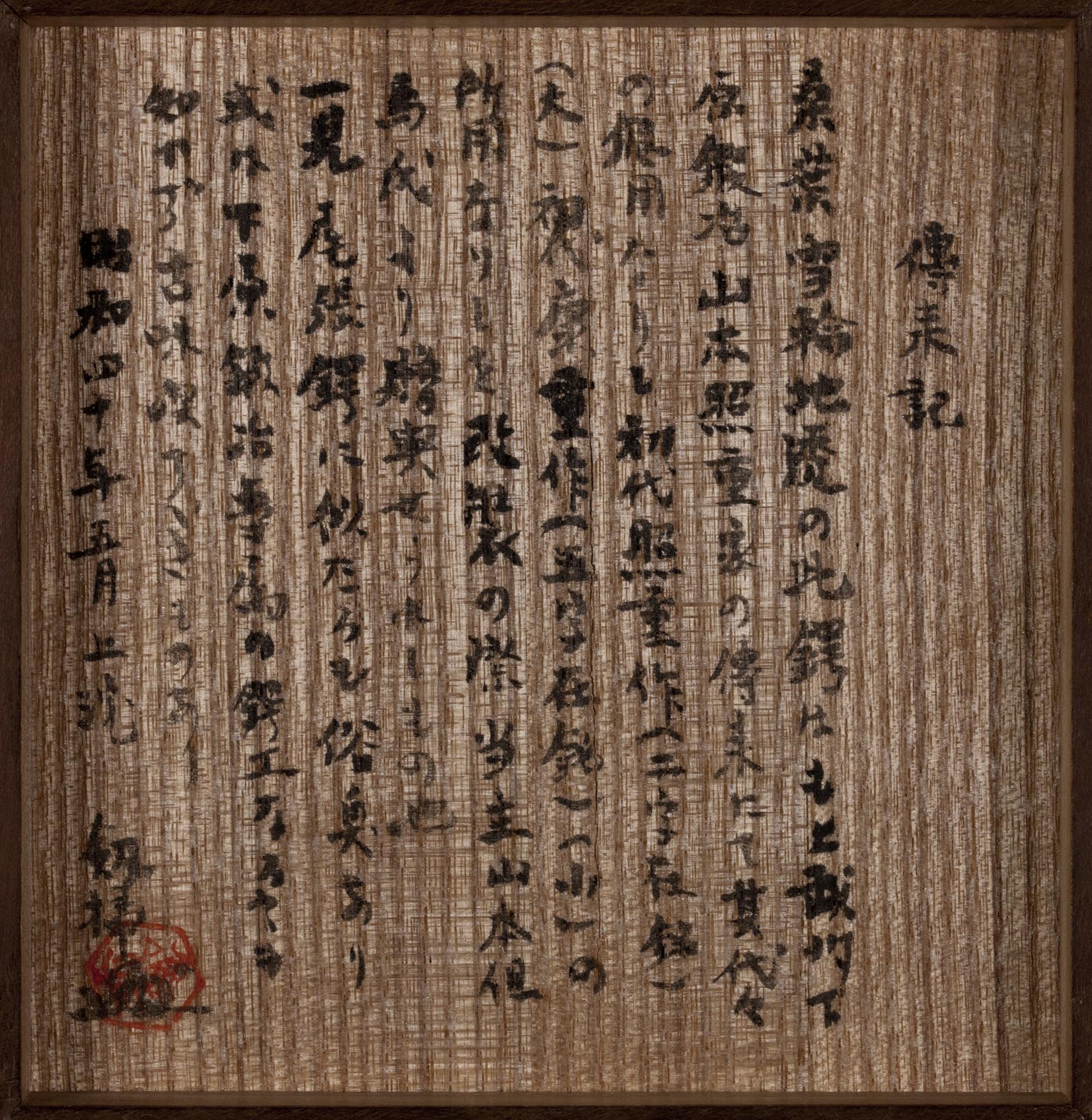

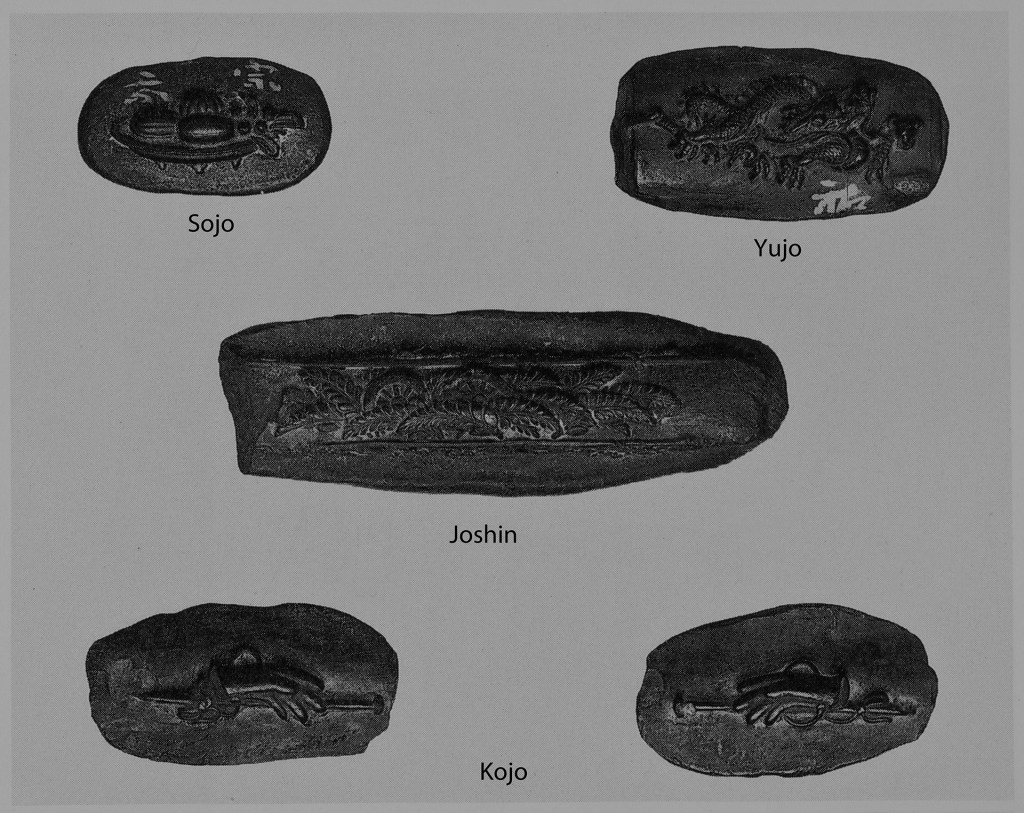

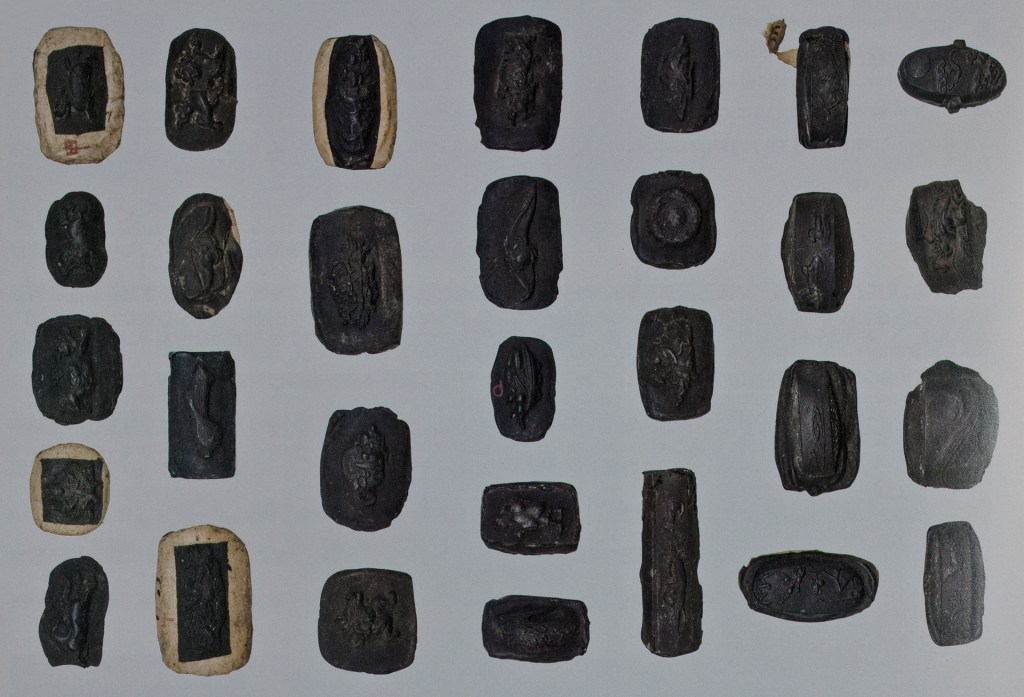

I picked up a group of 20 of these, and only one has (indecipherable) writing on the back. However, there are published examples that are clearly labeled with the names of the makers which would be very handy things to have. Books on the Goto family have the same set of photos of the various tools, weights and seals they used. They also include this valuable reference material: yanigata facsimiles of work by the first four generations:

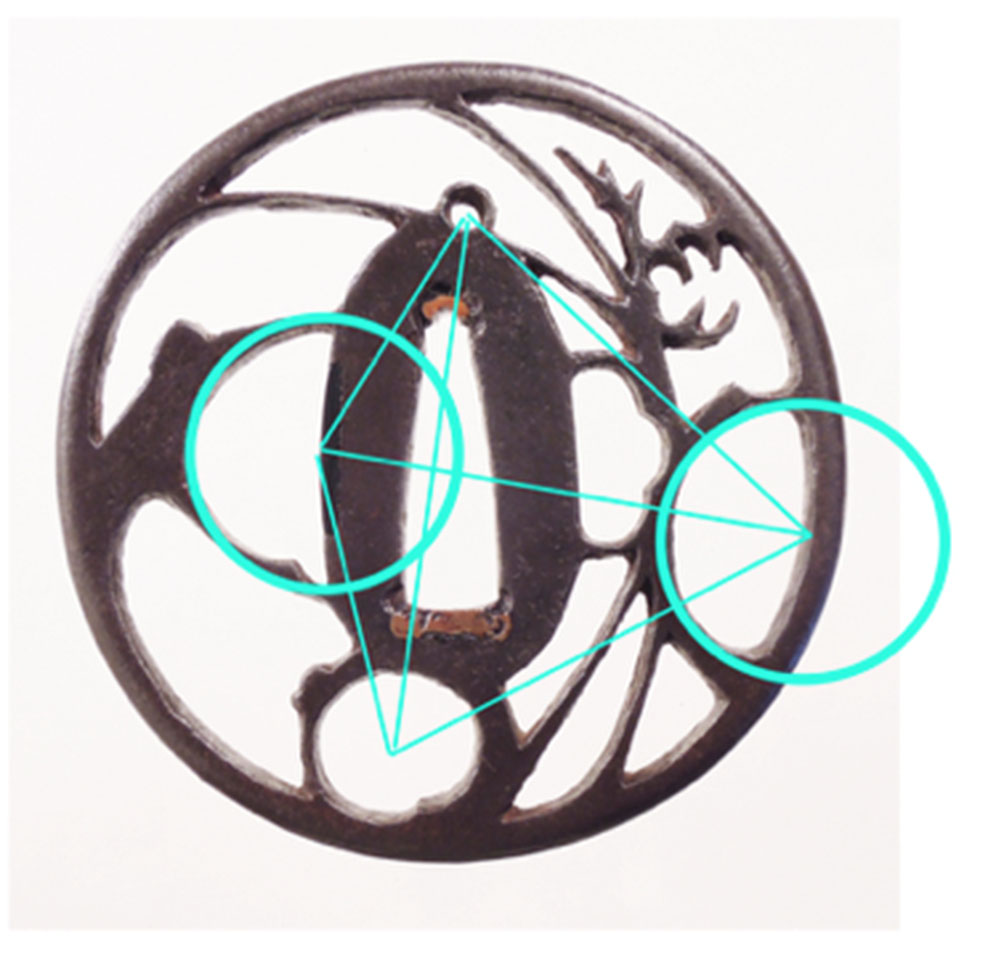

Having a full set of these on hand would have been very useful when the main branch family got together to kantei unsigned examples of their ancestors’ work and write origami. The detailed work visible is close to what was present in the originals. Oshigata work reasonably well for recording what a tsuba looked like, but are not much help with small fittings.

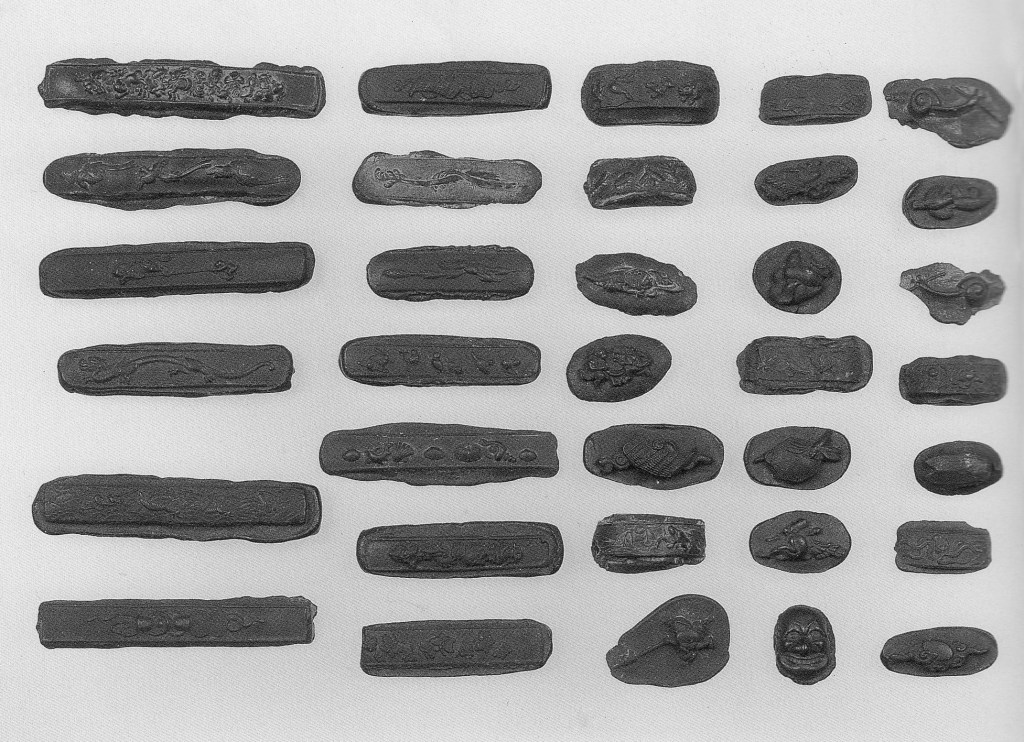

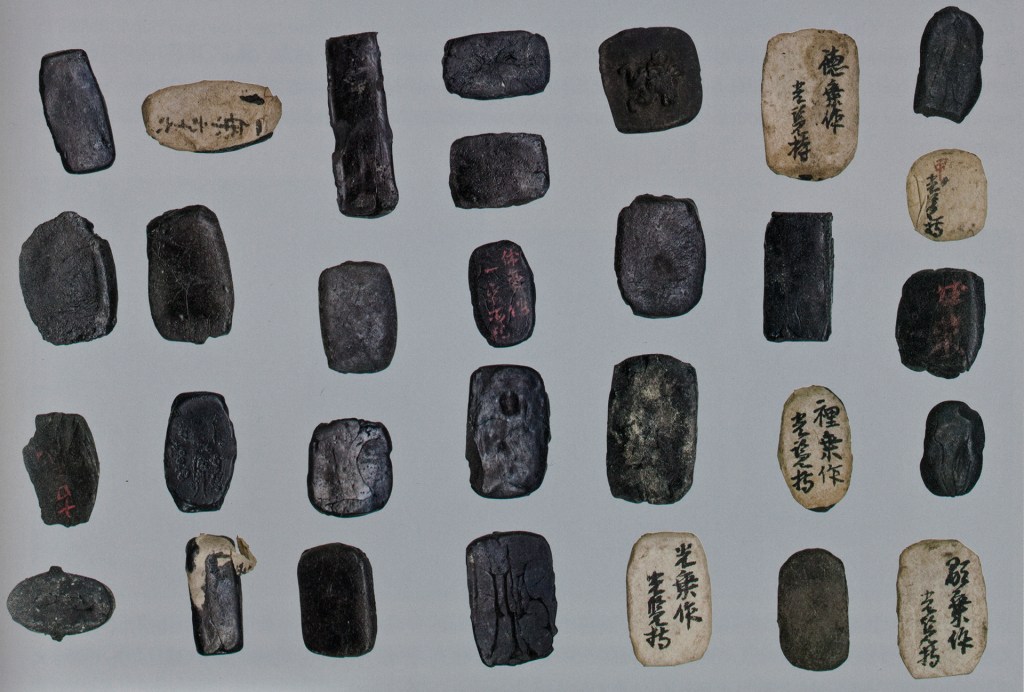

Another example set from the literature is published in the Ishikawa Prefectural History Museum’s 1997 catalog Katchû, Abumi, Tôsôgu, Kaga-han Gi to Dezain .

And these are from the Osaka Museum of History catalog of the Katsuya Shunichi collection:

Note that some of these appear to be partially wrapped in paper or perhaps painted with clay slip (likely the former based on the peeling one shown at top right and bottom left) . I don’t know if this is just for ease of writing and reading or if it also is intended to keep the edges from chipping. There are quite a few more in the Osaka catalog, but the images are smaller.

Another dragon kozuka from my group. Detail view follows.

Without any cues from the materials used, the backsides of menuki, etc., it is hard to say what group made many of these. It does put the focus on the details of the carving.

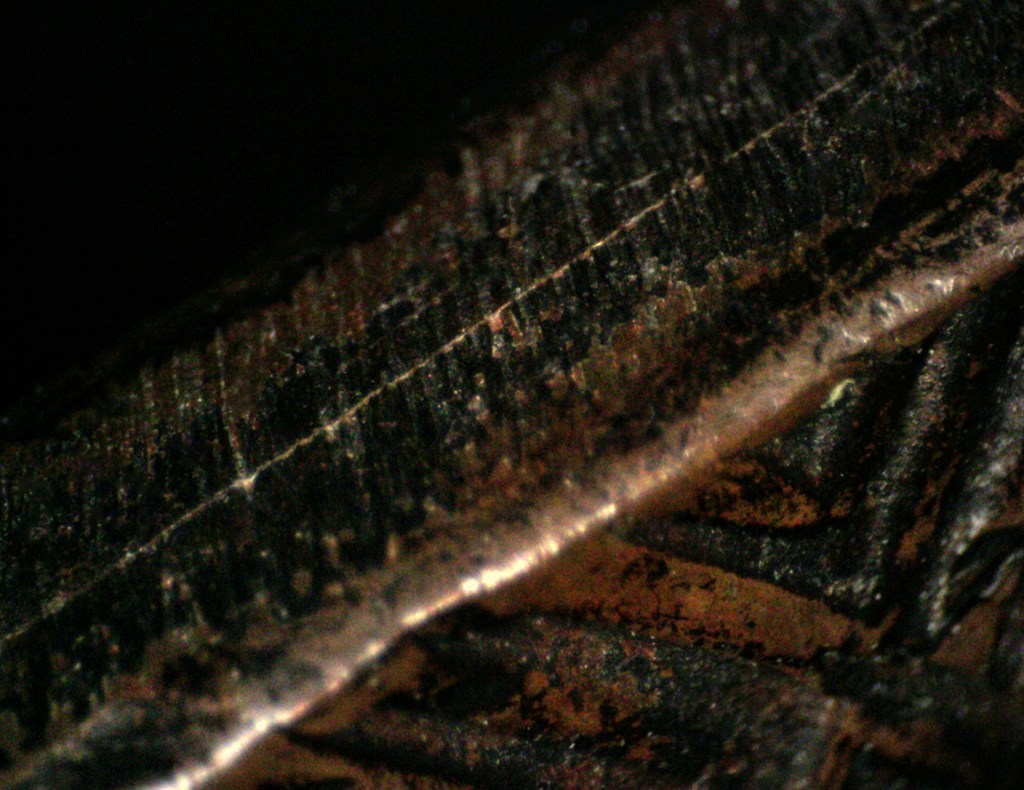

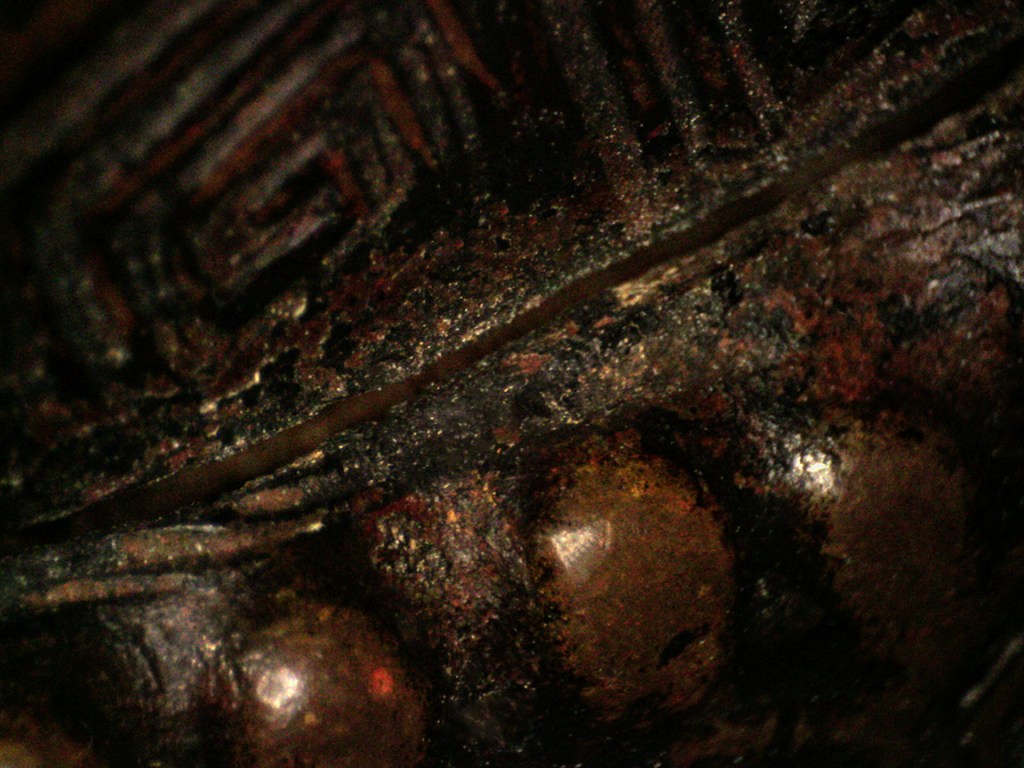

The lighter colored material is likely residue from the clay mold. It may have been left for visual contrast.

There is no sign of a frame around this pair of dragons so it is presumably from a very large menuki. Other than the pair of Kojo menuki illustrated near the top, the ones illustrated and the members of this group consist of singles. I don’t know if usually only one was made, or if the pair tended to get separated.

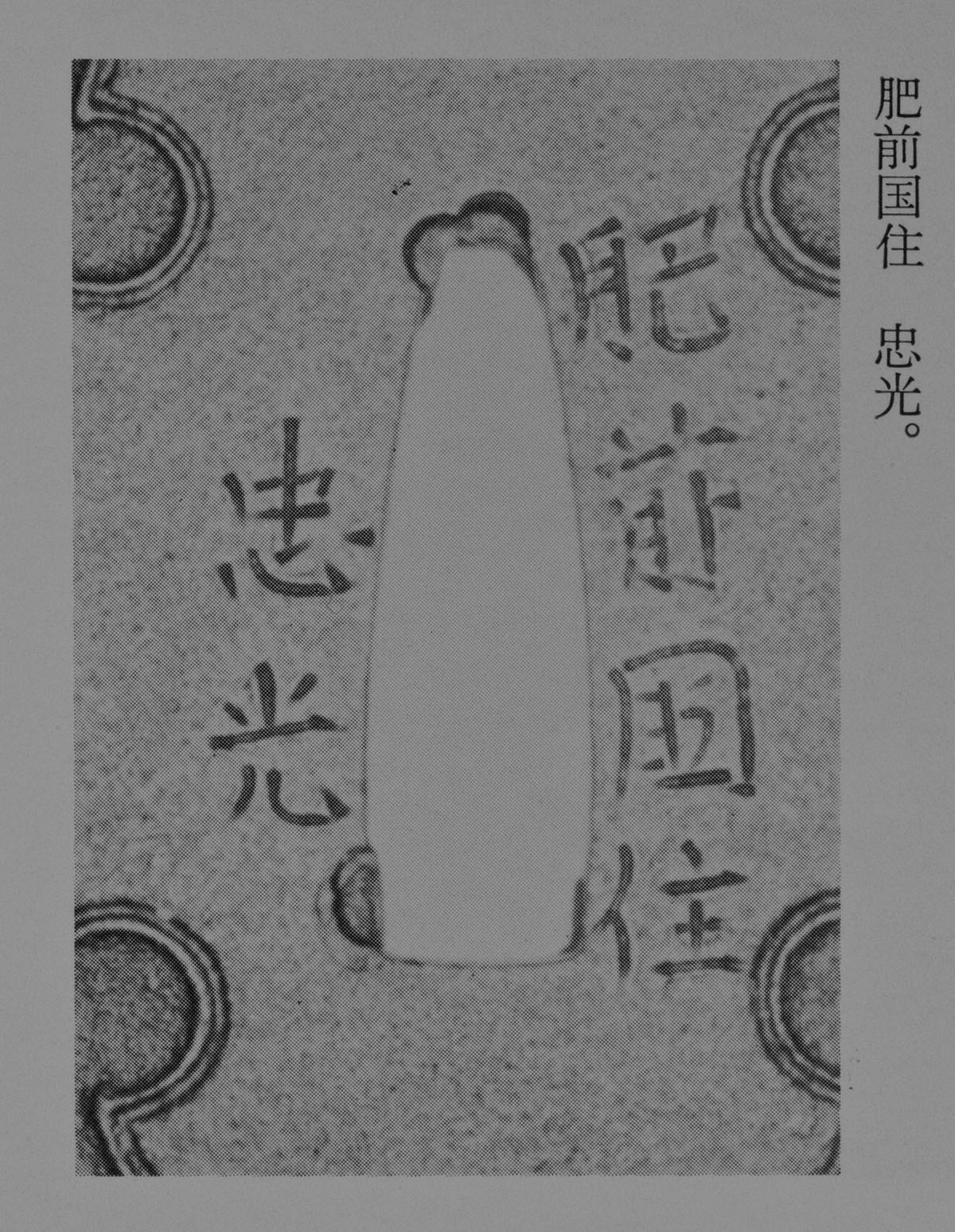

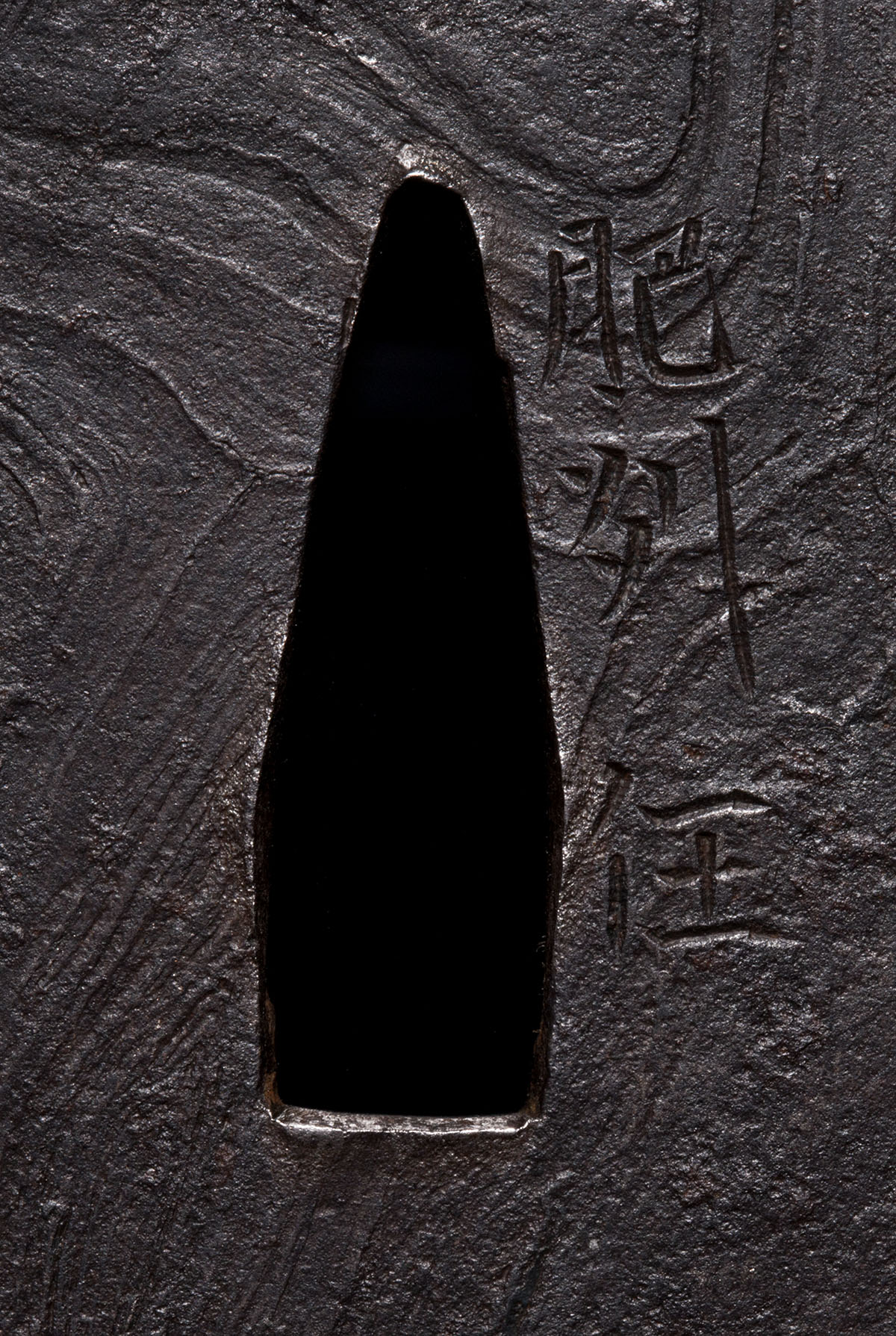

A nicely detailed menuki with inscription.

The resin used with these monkeys is quite a bit shinier and finer textured than the rest. It seems closer to a straight pine resin which makes me wonder if the others might be mixed with some granular material. The apparent strings or twisted wire appearing on left and center bottom of this one is also different. They wouldn’t be part of the actual menuki. Presumably it was part of the process of creating the yanigata . This one also has some residual mold or mold release material.

The backside of the monkeys also looks different. The shape and radius of the curves matches my thumbnail surprisingly well. I don’t see that on the others.

This fuchi is a bit on the rough side. A couple of pieces that I’m not including here have very little detail. I don’t know if that is because the condition has deteriorated or if the original technique was lacking. While this is a simple process to describe, I’m sure that there were many ways for things to go wrong resulting in a poor yanigata.

A tanto-sized puppy motif kashira.

The impression here is quite deep but does not show signs of openings on the sides for shitodome, so perhaps it’s a kojiri rather than a kashira. It looks like the original work wasn’t of the highest quality. A fingerprint is visible on the left side wall.

A section from a small kozuka with a horse motif. The backside shows pressing with some sort of tool.

Sketchbooks and oshigata preserve valuable information, but yanigata are a step very much closer to being there. In the case of the Goto family I suspect that they were entirely for in house use. I wonder if machibori workers ever traded these or used them as samples to show prospective customers (although customers might not be impressed by those wavy kozuka).

Certainly there are sets of saya nuri “paint chips” that appear to be customer samples. Even some of the drawn and colored wooden forms of fittings including tsuba seem likely to be light weight, inexpensive “salesman samples.”

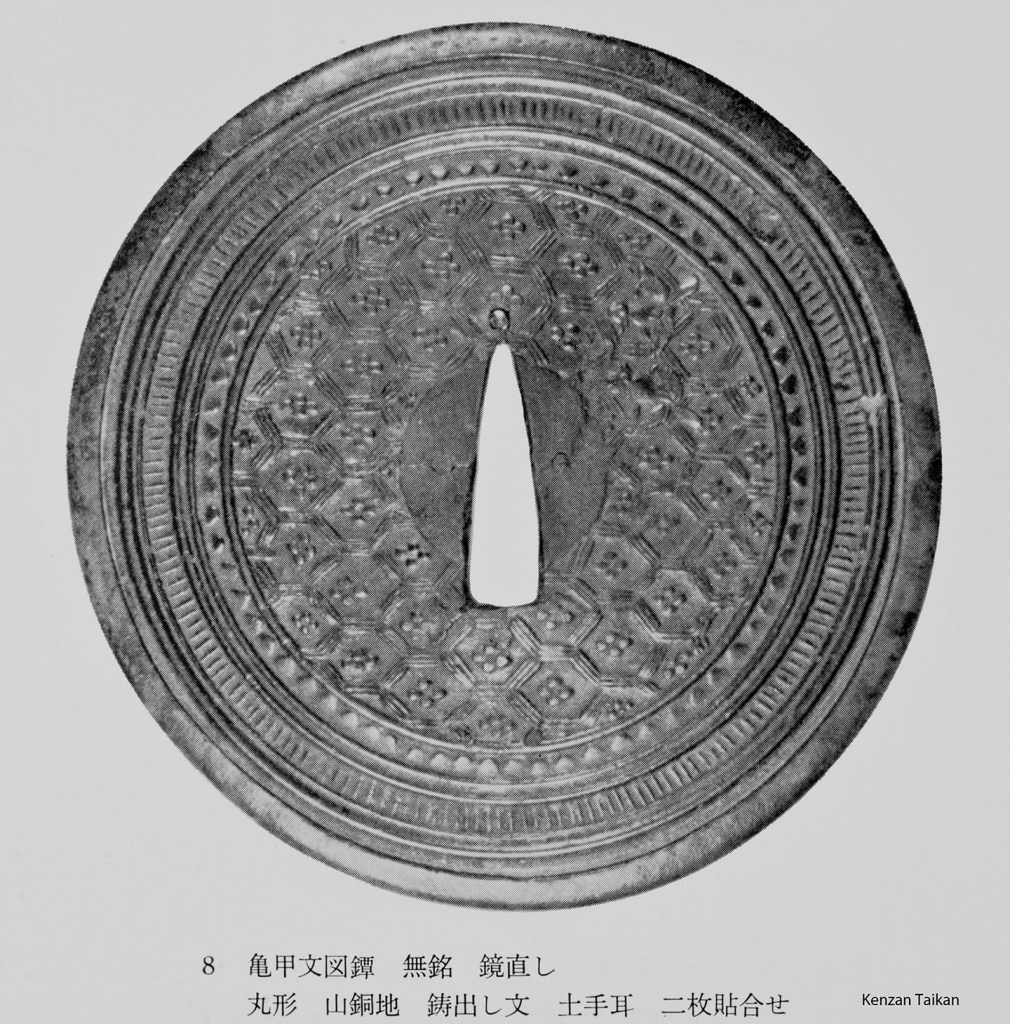

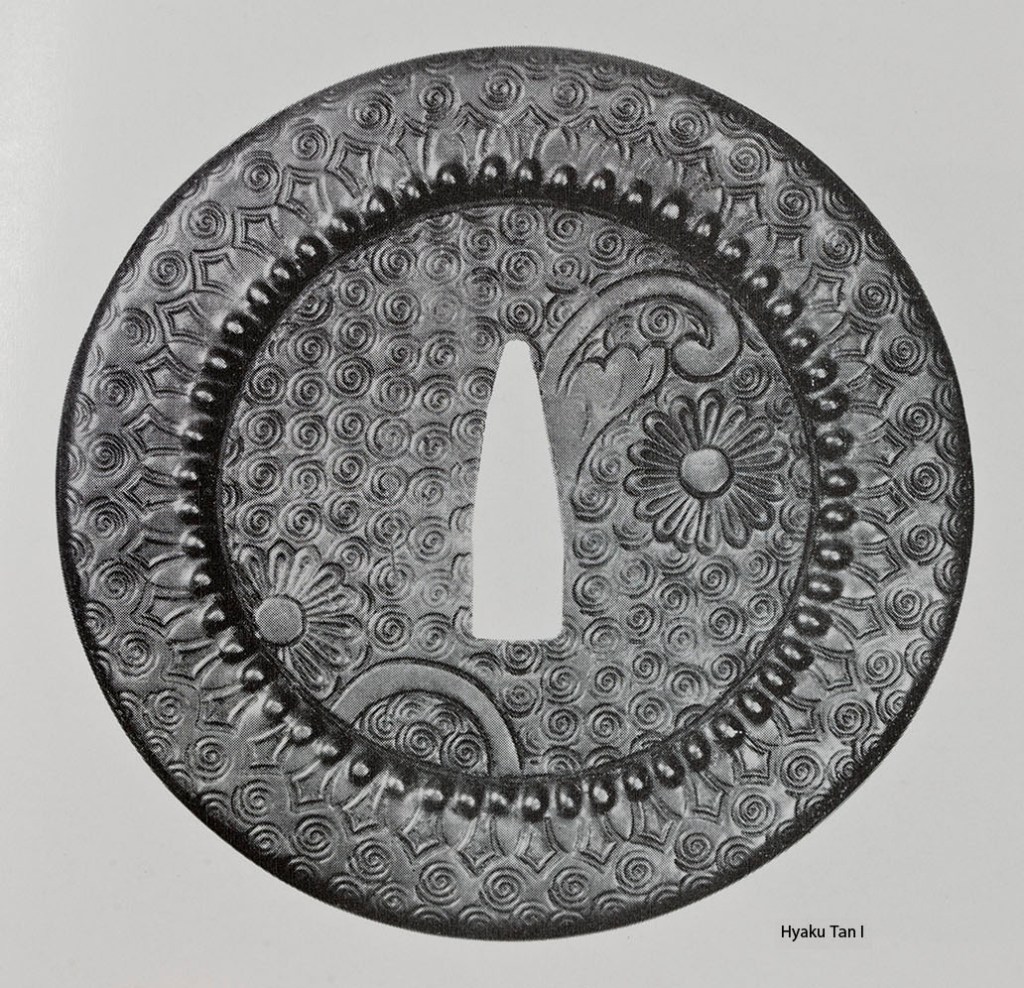

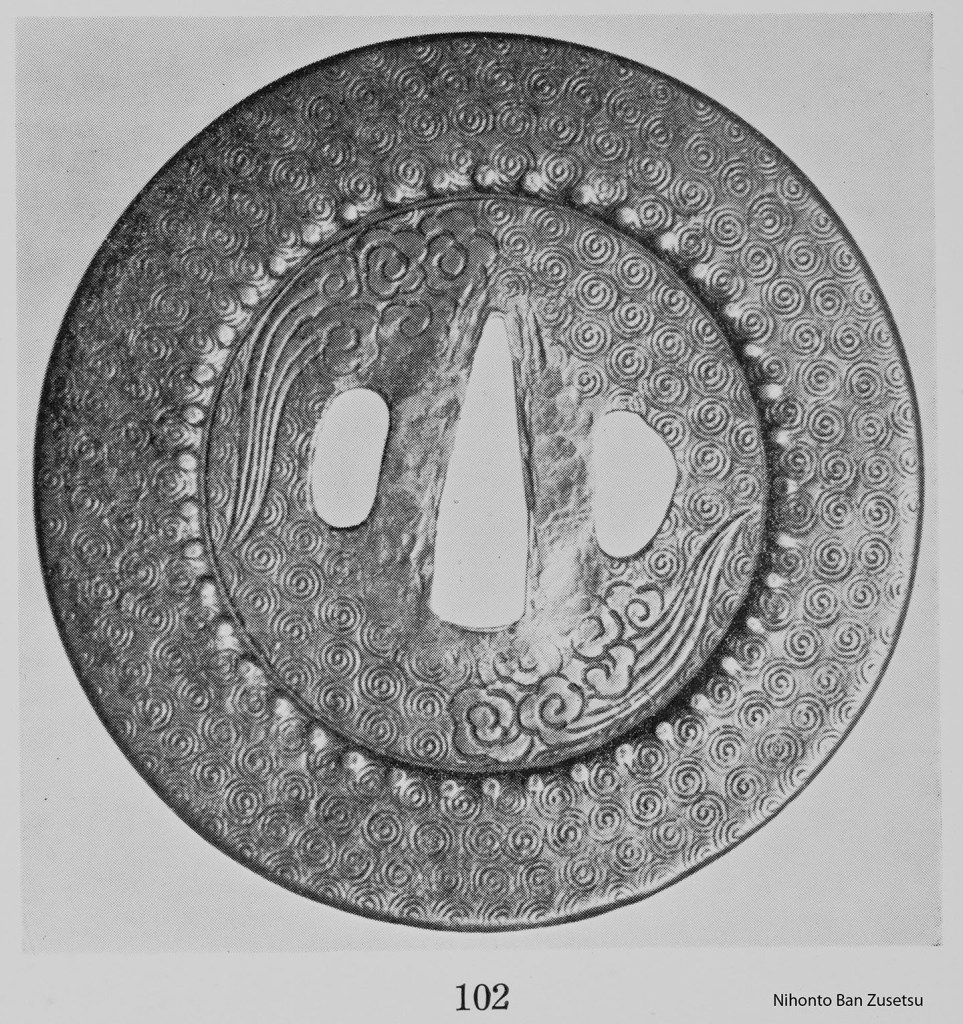

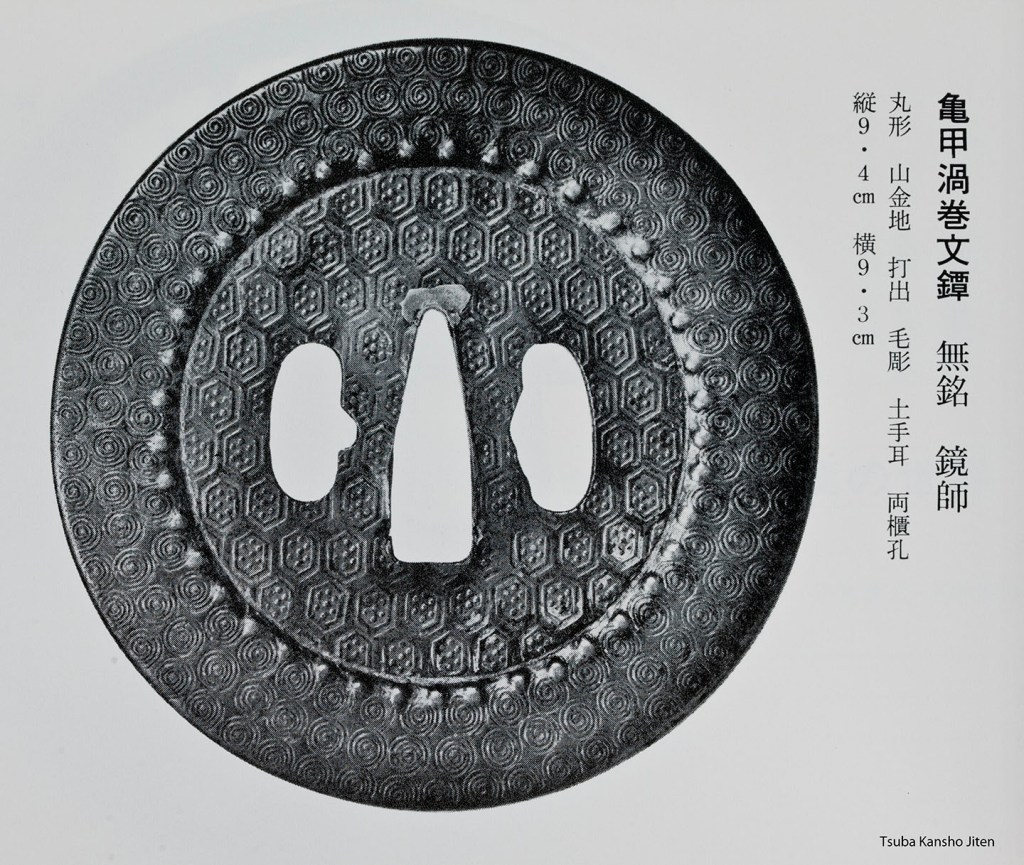

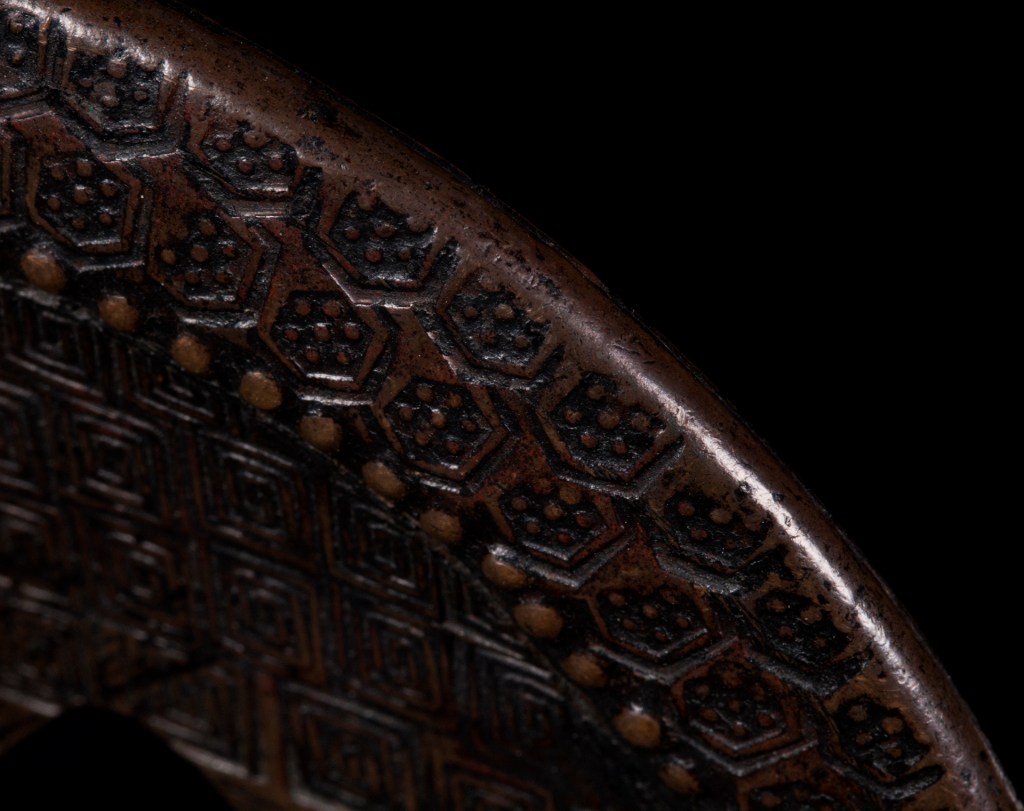

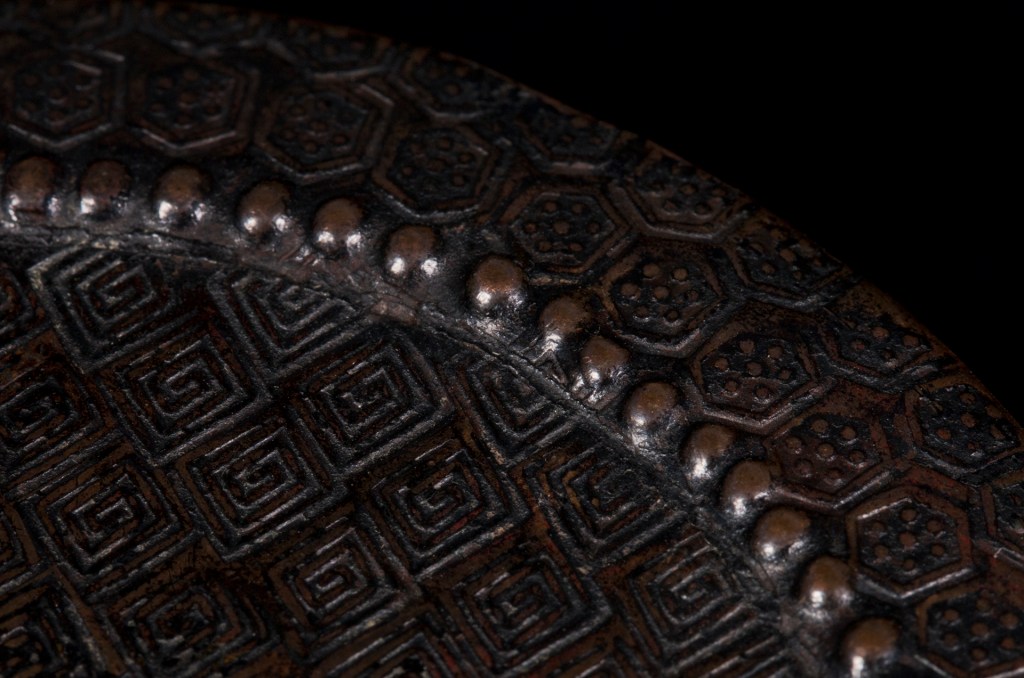

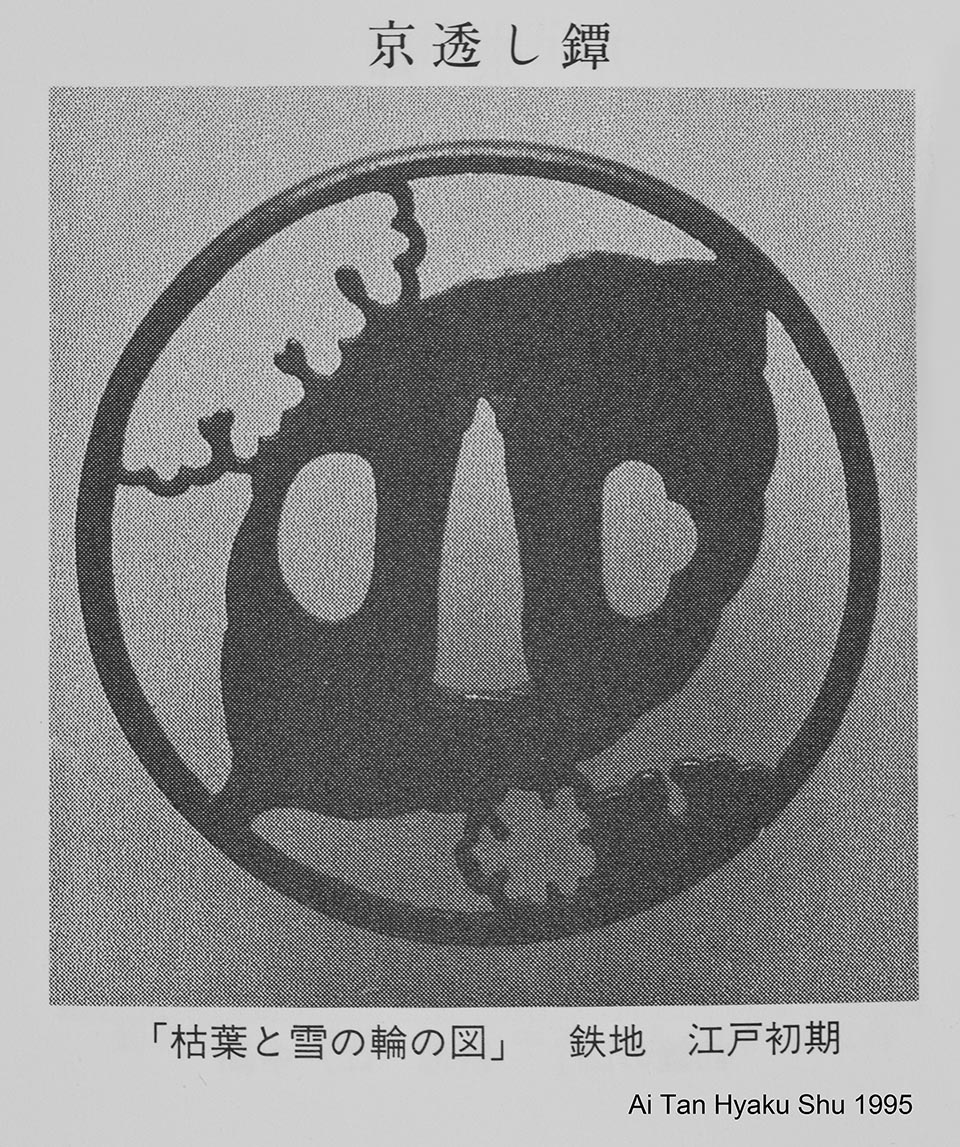

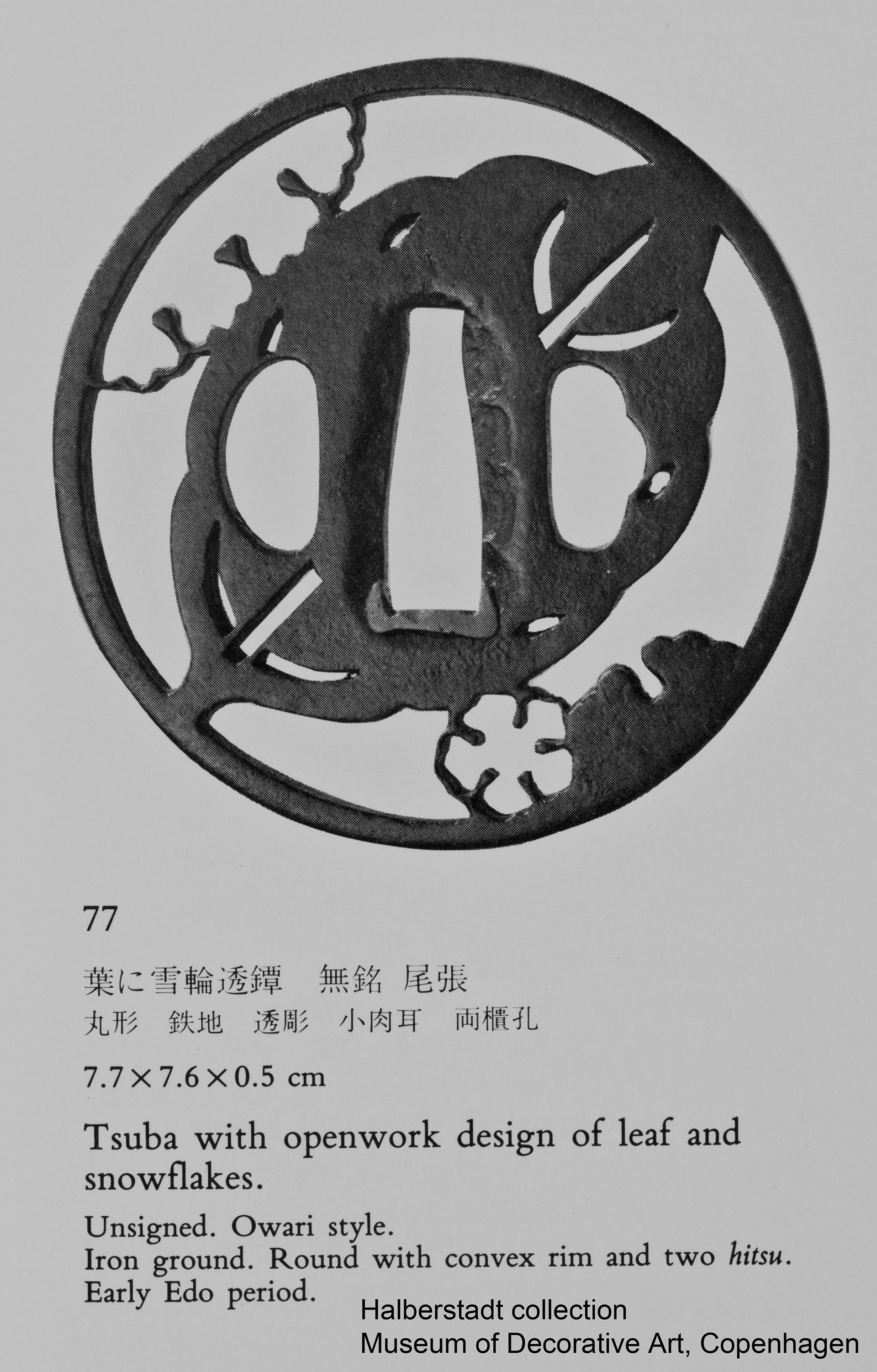

I haven’t seen any yanigata that appear to be taken from tsuba, but I did run across some illustrations recently of what appeared to be wet-molded paper copies pulled from tsuba – a sort of 3-D oshigata. They did not preserve the kind of detail seen here, though. Producing a full-tsuba yanigata may not have been technically practical, but capturing sections of decoration as done with some of the fuchi seems possible.

The small photos of these in the backs of kodogu books have always been intriguing, so it is exciting to get to examine some in person. Let me know if anyone has more information to share.